Beyond the Numbers: What Your BMI Actually Says About Your Health

What Your BMI Means for Your Health: Understanding BMI, Risks, and Healthy Weight

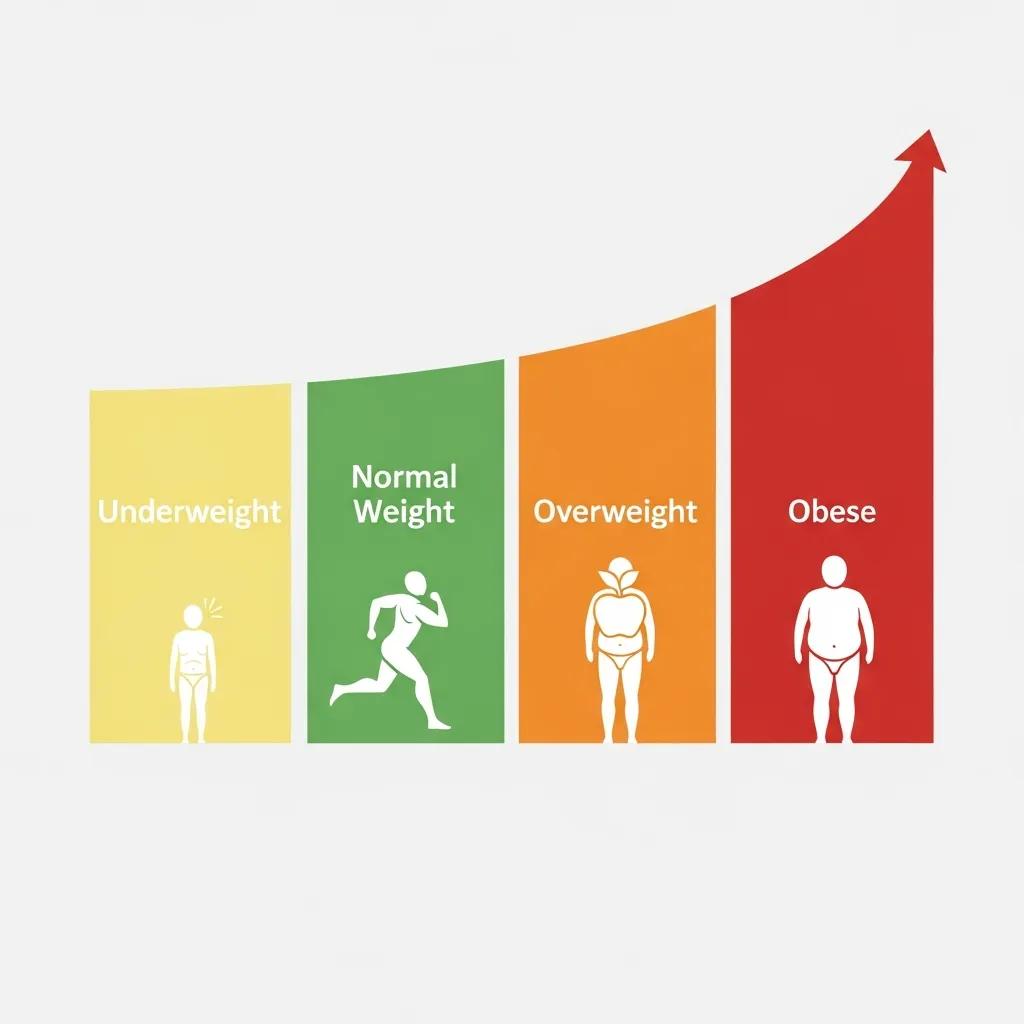

Body mass index (BMI) is a quick, easy number that links your weight and height to give a first look at body size and population-level risk. Calculated from weight and height, BMI sorts people into underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obesity categories—each of which is tied, on average, to different metabolic and cardiovascular risks. BMI doesn’t measure body composition directly, but it’s a useful screening tool that can flag when further checks—like blood glucose or lipid testing—are needed. This article walks through how BMI is calculated, the standard adult categories and what they mean, the main health risks tied to high and low BMI, how body fat percentage compares to BMI, and practical steps to reach or maintain a healthy BMI. You’ll find clear examples, easy-to-scan tables, and actionable advice—including when to ask a pharmacist or other clinician for personalized interpretation.

Understanding BMI: A Screening Tool for Healthy Weight and Health Risks

Body mass index (BMI) provides a simple estimate of body size by relating weight to height and serves as a first-step screen for healthy weight and population risk. Based on height and weight, BMI places adults into categories—underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obesity—that correlate with differing risks for metabolic and cardiovascular conditions. Though BMI does not measure fat versus muscle, it quickly highlights who may need further evaluation of metabolic markers such as blood glucose and lipids. This resource explains the calculation, standard adult categories, and how to use BMI responsibly alongside other measures.

Advantages and limitations of the body mass index (BMI) to assess adult obesity, Y Wu, 2024

What Is a Healthy BMI Range for Adults?

For most adults, a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m² is considered a healthy range. This window balances enough body reserve with generally lower cardiometabolic risk and better functional capacity. Clinicians use it as a starting point to decide who might benefit from further screening for metabolic syndrome or lifestyle support. Remember: BMI is a screening tool, not a diagnosis. Age, sex, ethnicity, and body composition all affect how BMI relates to health. If your BMI sits near a category boundary or you’re unsure what it means for you, talk with a pharmacist or other health professional for individualized guidance.

How Is BMI Calculated for Adults?

BMI reduces height and weight to a single number that approximates mass for height. The metric formula is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. In the imperial system, multiply pounds by 703 and divide by height in inches squared. These simple formulas let you calculate BMI without specialized tools, and many online calculators automate the math. Knowing the formulas helps you interpret small differences from rounding or unit conversion.

- Convert height and weight to metric units or use the imperial formula with the 703 multiplier.

- For metric: divide weight (kg) by height (m) squared; for imperial: multiply weight (lb) by 703 then divide by height (in) squared.

- Round to one decimal place for standard reporting and compare to category thresholds to interpret results.

Following these steps makes BMI calculation straightforward and supports accurate interpretation for adults.

What Are the Standard BMI Categories and Their Meanings?

Standard BMI categories describe adult weight status and offer a population-level signal of health risk. Underweight is <18.5 kg/m² and may point to malnutrition or illness; healthy weight is 18.5–24.9 kg/m² and generally indicates lower average chronic-disease risk; overweight is 25.0–29.9 kg/m² and suggests increased cardiometabolic risk; obesity begins at 30.0 kg/m² and is divided into Class I (30.0–34.9), Class II (35.0–39.9), and Class III (≥40.0) with rising levels of risk. These thresholds are screening cutoffs used in clinical practice and public health—useful for population guidance but not perfect predictors for every individual. The table below pairs categories with ranges and common health implications to make the numbers easy to scan.

| BMI Category | BMI Range (kg/m²) | Typical Health Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.5 | Possible nutrient deficiencies, lower bone density, and higher frailty risk |

| Healthy weight | 18.5–24.9 | Lower average risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | Increased risk of insulin resistance and osteoarthritis |

| Obesity (Class I–III) | ≥ 30.0 | Progressive increases in cardiometabolic and mortality risk |

This quick reference translates BMI numbers into practical meaning while reminding readers that personalized assessment refines individual risk.

What Are the Health Risks Associated with High BMI?

Higher BMI is linked with several chronic conditions driven by metabolic imbalance and higher inflammatory load, so BMI is a helpful cue to evaluate deeper metabolic markers. Excess body fat—especially visceral fat—promotes insulin resistance, unfavorable lipid patterns, and higher blood pressure, which together raise the chance of cardiovascular events and type 2 diabetes. Seeing these links helps prioritize assessments and interventions that target underlying metabolic processes rather than focusing solely on scale weight. Below is a compact list of common disease associations and a short look at mechanisms connecting BMI to disease.

- Type 2 diabetes: Excess adiposity fuels insulin resistance, raising blood glucose and diabetes risk.

- Cardiovascular disease: Higher BMI contributes to hypertension, atherogenic lipid profiles, and added cardiac workload.

- Certain cancers: Chronic inflammation and hormonal shifts tied to adiposity increase risk for cancers such as breast, colorectal, and endometrial.

- Osteoarthritis: Extra mechanical load and inflammatory signals accelerate joint breakdown.

- Sleep apnea: Fat around the neck and throat raises the chance of airway collapse during sleep.

These conditions illustrate how elevated BMI often clusters with metabolic syndrome; addressing weight and metabolic health can reduce multiple downstream risks and improve overall well-being.

Which Chronic Diseases Are Linked to High BMI?

High BMI ties into disease through both mechanical stress and metabolic dysfunction. Fat-driven inflammation increases cytokines that worsen insulin resistance and atherosclerosis—key drivers of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Extra weight also strains joints, contributing to osteoarthritis, and alters hormones in ways that can affect certain cancers. Understanding these shared pathways—insulin resistance, inflammation, and hemodynamic stress—helps target interventions such as dietary changes and metabolic monitoring to slow disease progression.

This mechanistic view supports focused screening of metabolic markers like fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid panels when BMI is elevated.

What Are the Risks of Low BMI?

Being underweight carries its own set of risks tied to limited nutritional reserves and reduced lean mass, affecting immunity, bone health, and recovery. Low BMI can signal malnutrition, chronic illness, or an eating disorder and is linked to higher fracture risk from lower bone mineral density and increased frailty in older adults. Inadequate calories and micronutrients also weaken immune defenses, raising infection risk. If a low BMI is unexplained or comes with declining function, seek prompt evaluation from a healthcare professional to find and treat underlying causes.

Both ends of the BMI spectrum deserve attention and individualized clinical responses.

How Does Body Fat Percentage Compare to BMI for Health Assessment?

Body fat percentage measures composition—the share of total mass that’s fat—while BMI measures mass relative to height; each answers a different question about health. Body fat percentage directly estimates adiposity and can separate muscular people from those with excess fat, while waist circumference tracks central fat that better predicts metabolic risk. Using BMI together with body fat percentage and waist circumference gives a fuller picture of metabolic health than any single measure alone. The table below clarifies when each measure is most useful and notes common limitations.

| Measure | What It Assesses / Limitation | When to Use / Typical Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | Mass relative to height; cannot separate fat from muscle | Quick population screening; healthy range 18.5–24.9 kg/m² |

| Body fat percentage | Direct estimate of adiposity; varies by sex and age | Use to assess composition; high risk often >25% men, >32% women (population-dependent) |

| Waist circumference | Proxy for central/visceral fat; better predictor of metabolic risk | Use when central obesity is a concern; thresholds vary by population (e.g., >102 cm men, >88 cm women in the US) |

Combining these measures improves interpretation for people with atypical body composition—such as athletes or older adults with low muscle mass. For readers wanting more detail on body-composition testing and metabolic health, offers educational resources and services to support personalized assessment.

Why Is BMI an Imperfect Measure of Health?

BMI can misclassify individuals because it treats all mass the same and ignores fat distribution—key factors for metabolic risk. An athlete with high muscle mass may have an elevated BMI but low body fat and low cardiometabolic risk, while an older adult with normal BMI can have low muscle and high fat percentage, increasing risk. Differences by age, sex, and ethnicity also change how BMI relates to disease, so clinicians interpret BMI in context and add other measures when needed.

Knowing these limitations helps readers see why BMI should prompt further evaluation rather than serve as a final answer.

Accuracy of BMI in Diagnosing Obesity: Limitations and Population Differences

Body mass index (BMI) is the most widely used measure to diagnose obesity, but its accuracy for detecting excess adiposity in the adult population is imperfect.

This cross-sectional analysis included 13,601 participants (ages 20–79.9; 49% men) from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Bioelectrical impedance estimated body fat percent (BF%). The diagnostic performance of BMI was compared with the World Health Organization reference for obesity (BF% >25% in men and >35% in women). Correlations between BMI and both BF% and lean mass were tested by sex and age groups, adjusted for race.

BMI-defined obesity (⩾30 kg m−2) was found in 19.1% of men and 24.7% of women, while BF%-defined obesity was present in 43.9% of men and 52.3% of women. A BMI⩾30 showed high specificity (men = 95%, 95% CI 94–96; women = 99%, 95% CI 98–100) but poor sensitivity (men = 36%, 95% CI 35–37; women = 49%, 95% CI 48–50) for detecting BF%-defined obesity. Diagnostic performance declined with age. In men, BMI correlated better with lean mass than BF%, while in women BMI correlated more with BF% than lean mass. In the intermediate BMI range (25–29.9 kg/m²), BMI often failed to distinguish between BF% and lean mass in both sexes.

Overall, the study concluded that BMI has limitations—especially for people in intermediate BMI ranges, men, and older adults. A BMI cutoff of ⩾30 kg/m² has good specificity but misses many people with excess fat. These findings may help explain why some studies observe better survival in overweight or mildly obese groups.

Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population, A Romero-Corral, 2008

What Other Measures Complement BMI for Better Health Insights?

Additional measures sharpen BMI’s screening signal and guide decisions about interventions. Waist circumference flags central adiposity linked to visceral fat risk, body fat percentage quantifies composition differences, and metabolic labs (fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipids) show physiologic consequences of excess adiposity. Thresholds and indications vary by population, but using two or more measures together improves risk stratification and helps tailor lifestyle or medical strategies.

When BMI may misclassify risk, combining measures gives a clearer path to personalized care and practical intervention planning.

How Can You Take Action to Maintain a Healthy BMI?

Reaching or keeping a healthy BMI involves sustainable lifestyle habits, tracking metabolic health, and getting professional support when needed. Effective strategies focus on food quality and portion control, building and preserving lean mass, improving sleep and stress, and setting small measurable goals—like 5–10% weight loss—to achieve meaningful health gains. Regularly monitoring weight, waist circumference, and relevant labs helps you track progress and adjust plans. The table below compares common intervention types and shows how lifestyle, medications, and pharmacy services can work together.

| Intervention Type | Role | Expected Benefit / Example Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle changes | Diet, exercise, sleep, stress reduction | Improves body composition and metabolic markers; supports sustainable weight loss |

| Pharmacological options | Prescription medications under clinician oversight | Can help with weight loss when combined with lifestyle changes |

| Pharmacy services | Counseling, medication review, supplements, compounding | Supports adherence, addresses drug interactions, and supplies targeted supplements |

Blending these approaches lets care match individual needs and risk profiles.

What Role Do Pharmacists Play in Managing BMI and Related Health Risks?

Pharmacists contribute to BMI management by reviewing medications that affect weight or metabolism, counseling on side effects and interactions, recommending evidence-based supplements when appropriate, and helping with prescription refills and personalized compounding. They can flag drugs that promote weight gain, coordinate with prescribers on alternatives, and provide adherence support that improves outcomes for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. For low-friction follow-up, Value Drugstore: Your Family Deserves the Best in Care offers telehealth consultations, prescription refills, natural supplement options, and personalized compounding to help patients manage BMI-related risks alongside their healthcare team.

Pharmacist-led care is a practical, patient-centered complement to lifestyle and clinical strategies for healthier weight.

Which Lifestyle Changes Support a Healthy BMI?

Sustainable improvements come from balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, good sleep, and stress management. Aim for a diet focused on whole foods, sensible portions, and enough protein to protect lean mass, paired with both aerobic exercise and resistance training to build strength and raise resting metabolism. Prioritize consistent sleep and simple stress-reduction practices—both influence appetite and insulin sensitivity. Small, measurable targets—such as 150 minutes of moderate activity each week and a 5–10% weight loss goal when appropriate—lead to meaningful reductions in cardiometabolic risk and support long-term maintenance.

Applied consistently and with professional guidance when needed, these evidence-based steps make healthy weight realistic and sustainable.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How does age affect BMI and health risks?

Age can significantly influence BMI and its associated health risks. As people age, body composition often changes, with a tendency to lose muscle mass and gain fat, even if weight remains stable. This shift can lead to a higher body fat percentage, which may not be accurately reflected by BMI alone. Older adults may have a normal BMI but still face increased health risks due to higher fat levels and lower muscle mass. Therefore, it’s essential to consider age alongside BMI when assessing health risks.

2. Can BMI be used for children and adolescents?

Yes, BMI can be used for children and adolescents, but it is interpreted differently than for adults. For younger populations, BMI is calculated in the same way, but the results are compared to age- and sex-specific growth charts. This approach accounts for the natural variations in body composition as children grow. Pediatricians often use BMI percentiles to determine whether a child is underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese, helping to identify potential health risks early on.

3. What lifestyle changes can help lower a high BMI?

To lower a high BMI, individuals should focus on sustainable lifestyle changes. This includes adopting a balanced diet rich in whole foods, fruits, and vegetables while reducing processed foods and sugars. Regular physical activity is crucial; aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise weekly, incorporating both aerobic and strength training. Additionally, improving sleep quality and managing stress can positively impact weight management. Setting realistic, incremental goals can also help maintain motivation and lead to lasting changes.

4. How does waist circumference relate to BMI?

Waist circumference is a valuable complement to BMI as it provides insight into central obesity, which is a significant risk factor for metabolic diseases. While BMI assesses overall body mass relative to height, waist circumference specifically measures abdominal fat, which is more closely linked to health risks like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Monitoring both metrics can offer a more comprehensive view of an individual’s health and help tailor interventions more effectively.

5. What should I do if my BMI is in the overweight or obese range?

If your BMI falls into the overweight or obese range, it’s advisable to consult a healthcare professional for personalized guidance. They can help assess your overall health, including metabolic markers and body composition. Developing a tailored plan that includes dietary changes, increased physical activity, and possibly behavioral therapy can be beneficial. Setting achievable goals, such as a 5-10% reduction in body weight, can lead to significant health improvements and lower associated risks.

6. Are there any medical conditions that can affect BMI readings?

Yes, certain medical conditions can affect BMI readings. For instance, conditions that lead to muscle loss, such as cancer or chronic illnesses, can result in a lower BMI despite high body fat levels. Conversely, individuals with high muscle mass, such as athletes, may have a higher BMI that does not accurately reflect their health status. It’s important to consider these factors and consult healthcare professionals for a more comprehensive assessment of health beyond BMI alone.

7. How can pharmacists assist in managing BMI-related health issues?

Pharmacists play a crucial role in managing BMI-related health issues by providing medication reviews, counseling on weight-affecting medications, and recommending lifestyle changes. They can help identify drugs that may contribute to weight gain and suggest alternatives. Additionally, pharmacists can offer support through personalized compounding, nutritional supplements, and adherence strategies to improve health outcomes. Their accessibility makes them valuable partners in a comprehensive approach to weight management and overall health.